MANASTIR LEPAVINA - SRPSKA PRAVOSLAVNA CRKVA

- BRATSTVO MANASTIRA

- ISTORIJA MANASTIRA

- KAKO DO MANASTIRA

- DUHOVNE POUKE

- MANASTIRSKA IZDANJA

- INTERNET BIBLIOTEKA

- INTERVJUI

- ČUDA BOŽJA

- PODVIŽNICI

- ARHIVA

- PITANJA I ODGOVORI

- UPUTSTVO ZA POKLONIKE

- PRAVOSLAVNI KALENDAR

- VIDEO PREZENTACIJE

- AUDIO - MANASTIR LEPAVINA

- PRAVOSLAVNA INTERNET TELEVIZIJA

- LINKOVI

AKATIST

ČUDOTVORNOJ IKONI MAJKE BOŽJE LEPAVINSKE

Pogledajte koji nam je rejting na Internetu?

PRIRODNE LEPOTE SVETA

...Sve si premudrošću stvorio" (Ps.103,24)

REZULTATI ANKETE O

RADIO BLAGOVESTI

VINJETE I UKRASNA SLOVA

VIZANTIJSKE IKONE FRESKE I VINJETE

RAZGOVOR SA ARHIMANDRITOM GAVRILOM O MODERNIM TEHNLOGIJAMA

KROZ MISIONARSKI RAD OCA GAVRILA

RELIGIJE I INTERNET

RAZGOVOR AHRIMANDRITA GAVRILA VUČKOVIĆA SA PRIM.DR RADETOM KALAMANDOM

VIRTUALNA PORODICA ARHIMANDRITA GAVRILA VUČKOVIĆA

MIKRO KNJIGA - INTERNET KNJIŽARA

DUHOVNA DECA SVOME OCU GAVRILU LEPAVINSKOM U ČAST POLA VEKA NJEGOVOG DUHOVNOG PODVIGA

PREKO FEJSBUKA DO DUHOVNOSTI

RAZGOVOR SA RADOMIROM VUČIĆEM

DIGITALNA TEHNOLOGIJA U MISIJI CRKVE

WEBMASTER NENAD BADOVINAC U JUTARNJEM PROGRAMU RADIJA SLOVOLJUBVE

WITNESS FOR AN APOSTLE: THE EVIDENCE FOR ST. THOMAS IN INDIA

Big Master Episode UpMovies Desi Sex Porn Video Indian Hot Couple Swathi Ranganathan Hardcore Porn Video Rumpa Porn Xvideos yang cute beauty girl sex with patner

For centuries, Indian Christian claims of an apostolic founding and of being the earliest Christian Church outside the Roman Empire were dismissed out of hand by western historians; both southern Indian tradition and the embellished second-century Syriac Acts of Thomas seemed to be little more than apocryphal legend. Although many of the Church Fathers spoke of St. Thomas’ apostolate to India, there was no historical evidence for the existence of the ruling kings mentioned in the Acts, nor were many of the ancient place names familiar to geographers. Although the Acts had circulated

For centuries, Indian Christian claims of an apostolic founding and of being the earliest Christian Church outside the Roman Empire were dismissed out of hand by western historians; both southern Indian tradition and the embellished second-century Syriac Acts of Thomas seemed to be little more than apocryphal legend. Although many of the Church Fathers spoke of St. Thomas’ apostolate to India, there was no historical evidence for the existence of the ruling kings mentioned in the Acts, nor were many of the ancient place names familiar to geographers. Although the Acts had circulatedsteadily through the Christian world since its appearance, both text and tradition lacked substantial material proof.

Even so, the Acts of Thomas was a fascinating narrative and began with the traditional description of the apostles dividing the world for missionary endeavors: “At that time we disciples were all in Jerusalem…and we divided the regions of the world that each one of us might go to the region that fell to his lot…India fell to Judas Thomas, who is also Didymas [Twin]; but he did not wish to go, saying that through weakness of flesh he could not travel and, “How can I, who am a Hebrew, go to preach the truth among the Indians.” …And….the Saviour appeared to him by night

and said… “Fear not, Thomas, go to India and preach the Word there, for my grace is with thee.” But he would not obey and said, “Send me where thou wilt – but somewhere else! For I am not going to the Indians” (Acts Thom. 1.1).

Unquestioning acquiescence was not a part of St. Thomas’ character and the other apostles, perhaps, weren’t terribly surprised. In the final three glimpses we have of him in the Gospel, St. Thomas urges the apostles to go die with Christ in Jerusalem, presses the Lord to explain precisely how they are to follow Him, and finally, refuses to believe the disciples’ assurance of Christ’s resurrection until he sees the risen Lord for himself.1 The apostle liked his definitions clear-cut, but once convinced, he was decisive. Powerless in the face of his outright refusal to go to India, Thomas’ fellowissionaries

appealed in prayer to the Lord Himself, Who was quick to respond. At the time of their gathering, one Abban (or Habban), an agent of an Indian King Gundaphar, was also in Jerusalem, looking for a

Mediterranean-trained carpenter to build a palace for the Indian-Parthian king. In the Acts the Lord appears to the agent, telling him that he has an architect-slave to sell, and the agent agrees: …and when the sale was completed the Saviour took Judas Thomas and led him to the merchant Abban….Abban…said, “Is this thy master?” And the apostle said, “Ye”… But he said, “I have bought thee from

him.” And the apostle was silent. On the following morning the apostle prayed… “I go whither thou wilt, Lord Jesus, thy will be done”… So they began their voyage. When they arrive in Gundaphar’s realm the king gives the apostle a large sum of money and sends him off to begin construction. Thomas, however, frees himself of the pecuniary burden by giving the money to the poor, and begins to tour the countryside teaching Christianity. Some months later, the king asks about the progress of the palace, and is told by his courtiers: “Neither has he built a palace, nor has he done anything else of what he promised to do, but he goes about the towns and villages, and if he has anything he gives it all to the poor, and he teaches a new God and heals the sick and drives out demons and does many other wonderful things; and we think he is a magician. But his works of compassion, and the healings which are wrought by him without reward, and moreover his simplicity and kindness and the quality of his faith show that he is righteous or an apostle of the new God whom he preaches (Acts of Thomas 1:19-20).

Ancient Cross at Chinnamali, pillar of original apostolic church.

for inducing a local queen to avow marital abstinence, while Indian tradition insists that his death was instigated by angry Brahmans for preaching Christianity. The place, however, is agreed upon (Mylapore near Madras in Tamil Nadu State, India), as is the date of his martyrdom: he was struck with a spear on December 19, A.D. 72, and reposed three days later on December 21.2 The remaining early copies of the second-century Syriac Acts of Thomas are in many places embellished and fanciful, with gnostic novelties such as Thomas being alluded to as the “twin” of the Lord. This, along with a lack of concurring historical evidence, caused its wholesale rejection by western historians until, astonishingly, in 1834 an explorer turned up a hoard of ancient coins in Afghanistan’s Kabul Valley. Many bore the pictures and names of forgotten kings, some of them stamped in Greek and old Indian script with the name Gundaphar in various spellings. Within a few decades Gundaphar

coins were found from Bactria to the Punjab, and several dozen are now exhibited in the British and Calcutta Museums, dated to the first century A.D. At the end of the nineteenth century, a stone tablet was uncovered in ruins near Peshawar inscribed with lines from an Indo-Bactrian language. According to orientalist historian Samuel Moffett, the inscription “not only named King Gundaphar, but it dated him squarely in the early first century A.D., making him a contemporary of the apostle Thomas just as the muchmaligned Acts of Thomas had described him. According to the dates on the

tablet he would have been ruling in 45 or 46, very close to the traditional dates of St. Thomas’ arrival in India.”3 Finally, in the late nineteenth century the writings of the pilgrim-abbess Egeria were brought to light. In her travels to the Holy Land, Syria, Lebanon, and Egypt during the period of 381-384 she states: “In the name of Christ our God we arrived safely at Edessa. On arriving there we visited without delay the church and the martyrium of Saint Thomas [the Apostle]. In accordance with our usage we there performed our devotions and what else we are accustomed to do when visiting holy places. We also read portions of the Acts of Saint Thomas [at his Shrine]. The church is indeed a large and handsome edifice of a new design, and it is really worthy to be the House of God…”

[2 The Orthodox calendar celebrates St. Thomas the Apostle on October 6, on the second Sunday of Pascha, and on June 20 (the translation of his right hand from Edessa to Constantinople in 920.) The Roman Catholic and many Eastern Christian Churches celebrate him on July 3, the ancient Edessan feast, probably commemorating the relics’ arrival from India to Edessa in or before the third century. Indian Christians of various denominations commemorate his spearing on December 19, and his repose on December 21.

3 Moffett, Samuel, A History of Christianity in Asia, Vol I, Orbis Books, NY, 1998.]

Early twentieth-century Dominican commentators followed the discovery with the forceful argument that Egeria would hardly have been reading “the distorted Gnostic edition that has come down to us, but a copy of the Acts accepted and recognized as catholic and genuine by the Christians of that age…. This offers clear proof that there were copies which had not been distorted and utilized for Gnostic purposes.… The Acts the pilgrim carried with her were in Greek, as also was the Codex of the Scriptures, as shown from her quotations.”

With these two monumental discoveries, complaints of insufficient evidence and an uncertain text no longer hold the field. Although historians may continue to be sceptical, the evidence must be dealt with. Trade, Diplomacy, and Colonies It has long been known that there was widespread trade between the Roman Empire, Mediterranean peoples, and India. The subcontinent was visited a thousand years before Christ by King Solomon’s warships, and according to the first-century Roman historian Pliny, Malabar coastal traders ranged the Arab Sea, the Red Sea, Egypt, and Aden, with Muziris as

their port. Not only did the Roman Empire send diplomatic missions to India for hundreds of years, but first-century Jewish settlements in India are well-documented. Historians now believe that it would not have been unusual or even difficult for a first-century Jew to take ship for India. Moffett pushes it even further: “India was quite possibly more open to direct communication with the West in the first two centuries of the Christian era than in any other period of history before the coming of the Portuguese fifteen hundred years later…. Perhaps about A.D. 50 one such ship also carried a Jewish Christian missionary, a carpenter, to India, for carpenters are mentioned in documents of the time as being much in demand in the East. Greek carpenters were brought, for example, to build a

palace for a king in the southern Tamil kingdom of the Chola people.”

Early Church Fathers on St. Thomas’ Apostolate to India

There are many patristic references to St. Thomas in India. The most wellknown include: The Didascalia Apostolorum, from Edessa perhaps as early as 250 AD: “India and all its countries, and those bordering on it even to the farthest sea, received the Apostle’s Hand of Priesthood from Judas Thomas, who was guide and ruler in the church he built there… St. Gregory of Nazianzen (AD 329-390), who refers to Thomas along with the other apostles’ work in Homily 33, Against the Arians: “Were not the Apostles strangers amidst the many nations and countries over which they spread themselves, that the Gospel might penetrate into all parts, that no place might be void of the triple light or deprived of that truth, so that the cloud of ignorance among them even who sit in darkness and the shadow of death might be lifted? … Peter indeed may have belonged to Judea; but what had Paul in common with the gentiles, Luke with Achaia, Andrew with Epirus, John with Ephesus, Thomas with India, Mark with Italy? …(Contra Aranos et de Seipso Oratio) St. Ambrose of Milan (AD 333-397): Whence it came to pass that wearied of civil wars the supreme Roman command was offered to Julius

Augustus, and so internecine strife was brought to a close. This, in its way, admitted of the Apostles being sent without delay, according to the saying of our Lord Jesus: Going therefore, teach ye all nations (Matt. xxviii. 19). Even those kingdoms which were shut out by rugged mountains became accessible to them, as India to Thomas, Persia to Matthew. This also (viz., the internal peace) expanded the power of the empire of Rome over the whole world, and appeased dissensions and divisions among the peoples by securing peace, thus enabling the Apostles, at the beginning of the

church, to travel over many regions of the earth’ (Ambrose De Moribus). St. Jerome (AD 342-420): “Jesus dwelt in all places; with Thomas in India, with Peter in Rome, with Paul in Illyricum, with Titus in Crete with Andrew in Achaia, with each apostolic man in each and all countries” (Epistles of St. Jerome). St. Paulinus of Nola (AD 354-431): “So God, bestowing his holy gifts on all lands, sent his Apostles to the great cities of the world. To the Patrians he sent Andrew, to John the charge at Ephesus he gave of Europe and Asia, their errors to repel with effulgence of light. Parthia receives

Matthew, India Thomas, Libya Thaddaeus and Phrygia Philip” (Migne, P-L., vol. 1xi. col. 514). St. Gregory, the Bishop of Tours (AD 538-593) in his De Gloria Martyrum writes: “Thomas, the Apostle, according to the history of his passion, is declared to have suffered in India. After a long time his body was taken into a city which they called Edessa in Syria and there buried. Therefore, in that Indian place where he first rested there is a monastery and a church of wonderful size, and carefully adorned and arrayed”.

Other References to Early Indian Christianity Include:

The testimonies of Bishop Eusebius of Caesarea (+340) and St. Jerome (+420) detailing the mission of St. Pantaenus, a Christian philosopher sent by Bishop Demetrius of Alexandria, “to preach Christ to the Brahmins and to the philosophers of India” in A.D. 190. Both writers affirm the tradition of first-century Christianity in India, although Eusebius follows the Alexandrian tradition in reporting that St. Pantaenus met Indian Christians who told him that they had been given a Hebrew version of St. Matthew’s gospel by the Apostle Bartholomew. (Although there is no reason that Sts. Bartholomew and Thomas could not have both been in India, Eusebius is almost alone among the Fathers in claiming Bartholomew, who is usually believed to have preached in Armenia. Some historians feel that in some cases, the geographical term India, could have also included parts of Ethiopia and Arabia Felix.) Theophilus (surnamed “the Indian”) is another contemporary fourth-century source. During the reign of Emperor Constantine the Great, the young Theophilus was sent from India as a political hostage to the Romans. Constantine’s son, Constantius, later sent him on a mission to Arabia Felix

and Abyssinia (Ethiopia). His travels are recorded by Philostorgius, an Arian Greek Church historian, who relates that after fulfilling his mission, Theophilus sailed to his island home off the Indian coast. From there he visited other parts of India, reforming many things – for the Christians of the place heard the reading of the Gospel sitting, etc. His references to a body of Christians with a church, priest, and liturgy could only apply to a Christian Church and faithful who inhabited the west coastal region of Malabar, and whose liturgy was in Syriac. Long-held Indian traditions claim that St. Thomas ordained two bishops, Kepha for Malabar and Paul for Coromandal (Mylapore), the first hierarchs of India. The first historical mention of an Indian hierarch after the legalization of Christianity is John the Persian, who was present at the Council of Nicea (325) and signed the degrees of the Council with the title: John the Persian, over the churches in all Persia and Great India. It is not known when India began having resident bishops, but in 530 Cosmas Indicopleustes writes in his “topographia” (a cultural survey of the time) that there are Christians “in Male (Malabar) where the pepper grows.” He adds that the Christians of Ceylon, whom he specifies as Persians, and “those of Malabar” (whom he does not identify, which presupposes that they were native Indians) had a bishop residing at Caliana (Kalyan), ordained in Persia, and one likewise on the island of Socotra. St. Gregory of Tours (Glor. Mart.), writing before 590, reports that a certain Theodore, perhaps a Syrian pilgrim, who came to venerate the relics of St. Martin of Tours during Gregory’s episcopacy and had also visited India, told him that where the relics of Thomas the Apostle rested, “stands a monastery and a church of striking dimensions and elaborately adorned.”… “After a long interval of time these remains had been removed thence to the city of Edessa.” Theodore visited both tombs, in India and Edessa.

St. Bede the Venerable (673-735): “The Apostles of Christ, who were to be the preachers of the faith and teachers of the nations, received their allotted charges in distinct parts of the world. Peter receives Rome; Andrew, Achaia; James, Spain; Thomas, India; John, Asia….” (Opera omnia, Coloniae Agrippinae) The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, relating the events of the early history of England, tells of a vow made by King Alfred as he defended the city of London, besieged by the heathen Danes. In fulfillment of this vow he sent an embassy with gifts to Rome, and another to India to the shrine of the

Apostle Thomas: “The year 883[884]. In this year… Marinus, the Pope, then sent lignum Domini [a relic of the Cross] to King Alfred. And in the same year Sighelm and Aethâlstan conveyed to Rome the alms which the king had vowed [to send] thither, and also to India to Saint Thomas and Saint Bartholomew, when they sat down against the army at London; and there, God be thanked, their prayer was very successful, after that vow.”

A Syrian ecclesiastical calender of extremely early date confirms the translation of the relics. The entry reads: 3 July, St. Thomas who was pierced with a lance in India. His body is at Urhai [the ancient name of Edessa] having been brought there by the merchant Khabin. A great festival. Two points support the note’s antiquity: the early name given to Edessa and the fact that the translation of the apostle’s relics was so fresh that the name of the individual who had brought them was still remembered. Contemporary eye-witness evidence that the relics had been translated from India to Edessa is provided by St. Ephrem the Syrian who came to Edessa after the surrender of Nisibis to the Persians in 363, living there until his repose in 373. In his forty-second Nisibene Hymn, St. Ephrem tells that the Apostle was put to death in India, and that his remains were subsequently enshrined in Edessa. The same tradition of St. Thomas is repeated in his other hymns: It was to a land of dark people he was sent, to clothe them by Baptism in white robes. His grateful dawn dispelled India’s painful darkness. It was his mission to espouse India to the Only-Begotten. The merchant is blessed for having so great a treasure. Edessa thus became the blessed city by possessing the greatest pearl India could yield…5

Marco Polo also visited India on his return from China in 1293. Of the apostle’s tomb he says, “The Body of Messer Saint Thomas the Apostle lies in this province of Maabar at a certain little town having no great population; ’tis a place where few traders go, because there is very little merchandise to be got there, and it is a place not very accessible. Both Christians and Saracens, however, greatly frequent it in pilgrimage. For the Saracens also do hold the Saint in great reverence, and say that he was one of their own Saracens and a great prophet, giving him the title of Avarian, which is as much to say “Holy Man.” The Christians who go thither in pilgrimage take of the earth from the place where the Saint was killed, and give a portion thereof to any one who is sick of a quartan or a tertian fever; and by the power of God and of Saint Thomas the sick man is incontinently cured. The earth I should tell you is red… The Christians who have charge of the Church have a great number of the Indian nut trees whereby they get their living; and they pay to one of those brother Kings six groats for each tree every month.” 6 Stone crosses of ancient date, bearing inscriptions in Pahlavi letters, have been pointed out in southern India for many centuries. One is in the Church of Mount St. Thomas, Mylapore7, its presence first chronicled by the Portuguese in 1547; the second is in the church of Kottayam, Malabar. The crosses are of Nestorian origin, and are engraved in bas-relief on the flat stone with ornamental decorations around the cross. Both bear the inscription: “In punishment by the cross was the suffering of this one, Who is the true Christ, God above and Guide ever pure.” Some archeologists have remarked on their resemblance to a Syro-Chinese Nestorian monument erected at Singan-fu, an ancient capital of China, to commemorate the arrival of Chaldean Nestorian missionaries to China in 636.

[5 According to both eastern and western traditions, some portions of relics were left in India at the time of the translation to Edessa and are now enshrined at the Cathedral of St. Thomas at Mylapore (Roman Catholic) and at the Church dedicated to St. Thomas on St. Thomas Mountain, the site of his martyrdom. The greater portion of relics remained in Edessa (now Urfa) until they were taken to Chios in 1258 and then to Ortona, Italy, where they are enshrined today in the local church. At the end of the fifth century, the right hand of St. Thomas was given by the Edessans to Constantinople, and a church built by Archbishop Anastasius (490-518) to enshrine them. Western Crusaders obtained the hand during the sack of Constantinople in the Fourth Crusade, and according to some reports it was taken to Hungary after the Fifth Crusade by Hungarian King Andrew II. There is no longer any trace of it in Hungary.

6 The Travels of Marco Polo: Vol. II, Chap. 28

7 The Mylapore cross on St. Thomas’ Mountain reportedly bled every December 18 from 1158 to 1774, with only a few years excepted.]

Local Indian Tradition

The Indian Christians or “Thomas Christians,” as they call themselves, still hold strongly to oral traditions of their founding by the apostle. These include the Ramban Pattu or Thomma Parvom, a song incorporating narratives from the Acts of Thomas. After forty-eight generations of oral tradition, the song was finally written down in 1600 by Rambaan Thomas, of the Malyakal family, a descendent of the first bishop ordained by St. Thomas, originally a Brahmin priest. The Margom Kali and Mappila Paattu are a series of songs of the Acts of Thomas and the history of the Malabar Church. They are sung with dances that are typical of the Syrian Christians. Some of these dance dramas are still performed in the open as part of church festivals. The Veadian Pattu is sung by a regional Hindu group (Veeradians) for Christian festivals, accompanying themselves on a local instrument called a villu. It is not known if these songs are based on early versions of the Acts of Thomas or are an independent tradition based on oral chronicles of the first Christians; in any case these traditions are universally held among Indian Christians. There were no written histories of Indian Christianity until the arrival of the Portuguese in the sixteenth century, just as India as a whole developed a written history only with the coming of the Arab Moslems. The British Museum holds a large collection of folio volumes containing manuscripts, letters, and reports of Portuguese Jesuit missions in India; among them a chronicle of the history of the Malabar coast. The report’s Jesuit author carefully compiled the oral traditions of these Christians,8 and traditional Indian beliefs in our own day collaborate his chronicle. The Portuguese narrative relates that after St. Thomas’ martyrdom, his disciples remained faithful for many centuries and the Church increased. Later, suffering persecution, war and famine, the St. Thomas Christians of the Malabar coast and Mylapore were scattered, and many returned to

paganism. The Christians from the Cochin region fared better, spreading from Coulac (Quilon) to Palur (Paleur), a village north of Malabar. Living under native princes who rarely interfered with their faith, they may not have suffered the severe persecutions that their brothers underwent on the coast. In the ninth century, a Syrian merchant, Mar Thoma Cana, was given permission by Cheruman Perumal, a leading rajah of Malabar, to settle and develop a Christian township that included many local Indian Christian families. They were also given a special civil status, records of which still exist.

[8 British Museum, folio volume 9853: beginning leaf 86 in pencil and 525 in ink.]

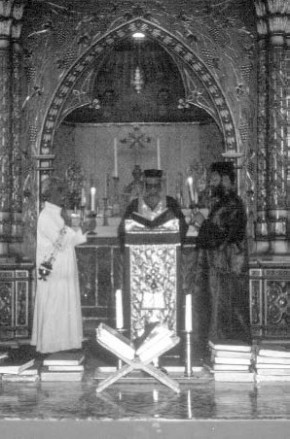

Pauumala – Gospel reading at evening service.

appear to have been Nestorian from the fifth century: for more than a millenium the Indian Church was provided with Persian-appointed hierarchs until this patronage declined in the sixteenth century. Today there are many Christian denominations present in India. The Orthodox Church under the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople has been active in northern India since 1982 and now numbers eighteen parishes and almost 4000 members.

source http://www.roadtoemmaus.net/back_issue_articles/RTE_21/WITNESS_FOR_AN_APOSTLE.pdf

Pročitano: 4282 puta

Njegova Svetost Patrijarh srpski g. Porfirije

MANJINSKI MOZAIK: IKONOGRAFSKI SPOMENICI LEPAVINSKI

ARHIMANDRIT GAVRILO U EMISIJI "POZITIVNO" NA HRT

PRILOG O INTERNET MISIONARENJU

ARHIMANDRITA GAVRILA VUČKOVIĆA U EMISIJI "DUHOVNI MOSTOVI" NA BHTV

MITROPOLIT JOVAN O MISIONARENJU SA NOVIM TEHNOLOGIJAMA U EMISIJI "ISKRE PRAVOSLAVLJA" RTRS

POSNA JELA PO IZBORU O. GAVRILA

"Hriste Bože, blagoslovi jelo i piće slugu Tvojih..."

ORTHODOX MISSION

PRAVOSLAVNA MISIJA

RECEPTI ZDRAVE I LEKOVITE HRANE

MANJINSKI MOZAIK

ČUDESNA ISCJELJENJA

MANASTIRSKO CVEĆE

IZ FOTO OBJEKTIVA JEROĐAKONA VASILIJA

REPORTAŽA O MANASTIRU LEPAVINI

O ČUDESNIM ISCELENJIMA

PREZENTACIJA KNJIGE "DUHOVNI RAZGOVORI-knjiga druga" Arhimandrita Gavrila (Vučkovića)

NA RADIJU SLOVOLJUBVE

VIDEO PREZENTACIJA "DUHOVNI RAZGOVORI - KNJIGA DRUGA"

ARHIMANDRITA GAVRILA (VUČKOVIĆA)

SPC HOLANDIJA

EPARHIJA ZAPADNOEVROPSKA

RADIO SLOVO LJUBVE

RADMILA MIŠEV O POLA VEKA DUHOVNOG PODVIGA OCA GAVRILA

PREZENTACIJA KNJIGE DUHOVNI RAZGOVORI

RAZGOVOR SA RADOMIROM VUČIĆEM

KLESARSKA RADIONICA AGIAZMA

SATELITSKA KARTA I VREMENSKA PROGNOZA